Aaron Rodgers—superstar quarterback, future Hall of Famer, human for whom revenge seems to be a dish best served always—is not alone. He has a lot of company, in fact, in the revenge space (which isn’t technically a thing but should be).

James Kimmel Jr. is on the phone from Connecticut. It’s Tuesday morning. Kimmel is, perhaps, America’s foremost authority on The Science of Revenge, which is the title of one groundbreaking book he has written. He is explaining how Rodgers is far from the only person to appear, to so many, to crave revenge.

“We all crave revenge,” Kimmel says. “Whether we imagine or really experience being treated unjustly, mistreated, shamed, humiliated, betrayed.”

How does one become a revenge expert, exactly?

Kimmel’s path there began with his own story. As a teenager, he said he came “within seconds” of committing a terrible act. He did not. Instead, he became a lawyer and practiced for two decades.

“These deep, psychological hurts activate inside our brains,” Kimmel says. “The brain hates pain, and it responds by wanting to rebalance itself with pleasure. The way we can do that most rapidly begins with [activating] the pleasure-and-reward circuitry that is the same circuitry of addiction.”

Kimmel ended his legal career when he realized that professional revenge—even exacted on behalf of his clients—was still revenge; the legalized version. “I found during that process that it started infecting my life,” he says. “It nearly destroyed my family and nearly killed me.” He soon began researching why human beings wanted to harm those who had hurt them.

“So you’re getting this dopamine pleasure,” he says. “And these are also areas of the brain that drive cravings. You get a brief burst of dopamine, and then it goes away, and you want the dopamine again, so you start seeking out either the drug or, in this case, the behavior.

“The revenge-seeking behavior.”

For the past 11 years, Kimmel researched this revenge science at the Yale School of Medicine. “And came upon this astonishing discovery that brain scans around the world were showing that, in fact, your brain on revenge looks like your brain on drugs,” he says. “That revenge-seeking is truly a powerful craving, and that revenge is the No. 1 root cause of almost all forms of human violence. It destroys our relationships, families, schools, communities and organizations. We can see revenge is really, seriously threatening to drive our nation apart.”

Add football teams to the wreckage revenge can wreak. But also understand that, while Kimmel knew of Rodgers’s debut revenge-a-palooza for the Steelers, he is not super familiar with Rodgers’s inclinations toward seeking revenge, however drastic they might be. He can speak in generalities. He can apply his research to public information. But he’s not pronouncing Rodgers a King Revenge of any sort.

We were interested in the concept, though. Rodgers doesn’t exactly conceal those he seeks revenge against. The Jets are but his latest example, because that was the last franchise Rodgers played for. And that exit, like so many of his exits, was downright strange, but not atypically so. More like the usual pattern: conflicting accounts of internal events, hard feelings on both sides, a split that, maybe, didn’t have to unfold like that one did.

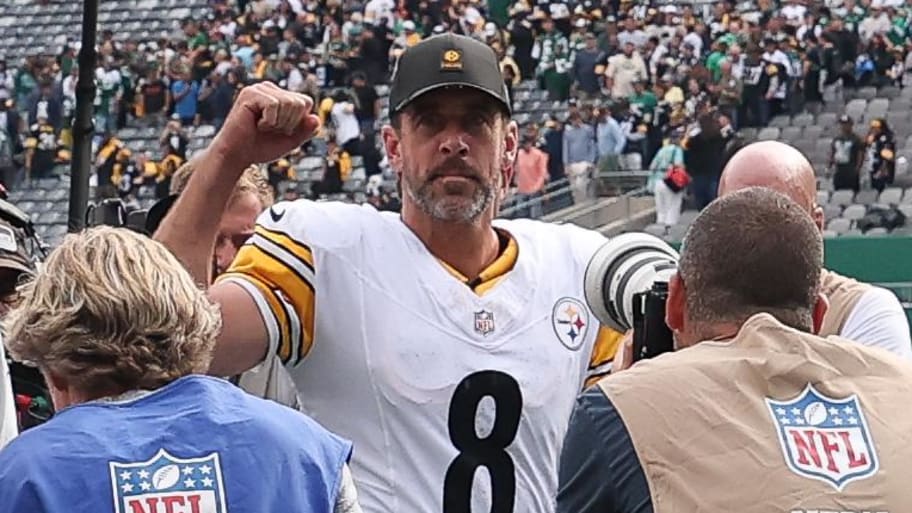

All that before the NFL’s schedule gods naturally made Steelers-Jets a Week 1 matchup. In the actual game, Rodgers obliterated, shredded and sought, yes, revenge against his former team’s talented and respected defense. He completed 22-of-30 attempts for an efficient 244 yards, with an 8.1 yards-per-play average. The exclamation point was four touchdown passes. But that was only the exclamation point on revenge itself. Revenge was the point. Rodgers made sure to note so afterward, when he told reporters it was “nice to remind those that I still can.”

Subtle? This is Aaron Rodgers. Never. High road? Typically not taken. Fair? Certainly. Fair but unnecessary to make so public, in such a, yeah, petty way? That seems fair, too. And it’s that pattern—the revenge so necessary for Rodgers against so many people and former employers and critics or skeptics or those who disagree, often quite strongly, with his views—that has seemed to bend wider, majority, public opinion to believe Rodgers seeks revenge far too often.

Part of me wondered if that was fair. If, perhaps, many who dislike Rodgers conflate some of his more dangerous opinions—on COVID-19 vaccines, for one—conflate what they don’t understand with a concept most people probably understand pretty well.

If anyone, Kimmel would at least provide the broad strokes for further examination. He offered a lot more than that, a counterargument of sorts, in favor of revenge that, if revenge must be exacted, period, is, in reality, healthy within the revenge space.

Kimmel is the founder and co-director of the Yale Collaborative for Motive Control Studies. He was the first expert in revenge to identify compulsive revenge as similar, even the same, as addiction. He created a brain disease model of revenge addiction—The No Justice System and its related Miracle Court App—and provided both for the public good, to anyone who wants them. He hopes his efforts prevent and treat violence. He runs a first-ever website, SavingCain.org, which was designed to avoid homicides and mass shootings. He developed “Warning Signs of a Revenge Attack”—those are also freely (widely) distributed.

As expected but in unexpected ways, Kimmel examined what can be gleaned objectively in Rodgers’s revenge calculus, and his take was borne from his experience, research and understanding. “So, going to Aaron Rodgers,” Kimmel says, “even though he may have had a habit of seeking revenge, about 100 percent of humans experience the desire for revenge when they’ve been wronged.”

He lays out the history involved, including the widely accepted notion that humans evolved into this universal (or nearly universal) trait. “It’s an adaptive strategy back to the ice age or earlier,” he says. “We all have it. It only becomes an addiction, though, if we can’t control it, despite the negative consequences.”

Rodgers to Kimmel’s point, but not the point he’s making, has had plenty of negative consequences for several of his revenge quests. None, to extend the same point, has appeared to deter his preferred method for vengeance in the slightest.

The Steelers’ opener was another layer of the same proof.

Kimmel doesn’t see this specific revenge act as any problem. Rodgers wanted revenge. Rodgers exacted revenge. Most feel better for that combination alone. “It’s fair and honest to point out that, in this case, he decided to use a more positive form of revenge-seeking that doesn’t harm other people and only uplifted him.”

Conversely, Rodgers cannot control how the wider sports public might view his latest vengeful act. He is aware enough of this pattern to have acknowledged and addressed it publicly. He has attempted to reclaim narratives that portray him in this light, as if this portrayal is also a negative thing. It might be. But Kimmel is saying that, in this instance—and in a lot of revenge instances with Rodgers, if applying the same thought process or methodology—it’s not.

“We know from research that acts of revenge-seeking that are designed to hurt other people usually don’t actually make us feel better,” Kimmel says. “Research shows that you often feel angrier after you engage in revenge-seeking. You feel an increased sense of anxiety, maybe depression. You also feel more fearful [of increasing the odds for retaliation].”

Sports, Kimmel says, are set up for braggadocio, theatrics, preening and, yes, revenge scenarios. They’re baked into the NFL’s genetic code. Both teams know before kickoff that, in the vast majority of games, one of them will win and the other will lose. The zero-sum nature is part of pro football’s massive popularity. The best revenge, then, is success—the phrase simultaneously a cliché and not a fact, but not a notion that’s hardly ever disputed.

Kimmel doesn’t use the phrase “positive revenge” that much. But he does apply it to Rodgers’s debut with Pittsburgh.

“Let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that Rodgers is a revenge addict,” Kimmel says. Please note: Kimmel is not and would never diagnose Rodgers as anything. “But he’s found a way, a useful way, to get his cake and eat it, too. He [has] gotten retaliation, without experiencing the negative consequences of harming them or harming himself in the process. It’s a win for him and, in sport, that’s why this is a pretty rare thing.”

Asked if he might impart any advice to Rodgers, were Rodgers, theoretically, asking for his viewpoint, Kimmel said he would congratulate Rodgers for “using his revenge desires to uplift himself.” He would also dispense the same advice he tells anyone who asks him for guidance: forgive fast and forgive often.

“You get so many benefits from doing that,” Kimmel says. “Not only do you shut down the pain, but who doesn’t want to take away pain from inside their brain? If I could give you a drug that could do that, you’d pay me trillions of dollars.”

He cites a colleague whose research indicates that forgiveness also reduces anxiety and depression, improves sleep, reduces cardiovascular events and reduces PTSD. And he lays out a counter-example that is as counterintuitive as his reasoned Rodgers take.

“Let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that Rodgers is a revenge addict. He [has] gotten retaliation, without experiencing the negative consequences of harming them or harming himself in the process. It’s a win for him and, in sport, that’s why this is a pretty rare thing.”James Kimmel Jr., revenge expert

For this, Kimmel points to the WNBA, where one Caitlin Clark teammate, in this case Sophie Cunningham, believed she saw officials not protecting Clark like other players or well enough at all, with a physical response against the Connecticut Sun in mid-June. In other words, Cunningham got revenge. For her getting, Cunningham’s follower counts jumped by seven digits on both TikTok and Instagram. Many tabbed her as a heroine. Kimmel understands that logic. But Cunningham’s revenge act was grounded in violence that could, that often does, incite more violence. Rodgers’s act, odd as this is to type, was not violent.

Kimmel sees his chosen expertise as a “big topic, with a lot of stake.” The hope he sees and feels is grounded in understanding that revenge-seeking and violence are biological processes. That means prevention plans, and treatment strategies, with reams of available, existing research on other addictions that can provide roadmaps.

“We’re also hard-wired to be able to forgive,” he says. “Just imagine. You shut down revenge cravings inside your head, and you activate your control circuitry yourself. Forgiveness is a wonder drug that stops pain and helps us heal.”

Will that alter Rodgers’s vengeful bent to professional football, media interviews and exits from NFL franchises? Not likely. But whether his behavior, in this aspect, needs to change should be the starting point of any Rodgers revenge debate.

This article was originally published on www.si.com as How Aaron Rodgers Used His Need to Exact Revenge in a Positive Way.