The New York Yankees’ path back to the World Series is as subtle as a six-ton wrecking ball. They are going to hit as many balls into the air as possible. They take an average of 69 swings per game. If two of them produce fly balls that go over the fence they win about 70 percent of the time.

It is that simple. The finer points of their game matter little. Like no other team in baseball except perhaps the Los Angeles Dodgers, their brothers in playing Airborne Baseball, the Yankees are leaning heavily into hitting the bottom third of the baseball to launch fly balls.

Up and down its lineup, New York has adopted swing changes and attack angles to get the ball in the air. They are doing so at such a preposterous rate that our traditional measurements of what makes a good October team—such as avoiding strikeouts and hitting with runners in scoring position—are meaningless. In fact, these 2025 Yankees are way worse at strikeouts and RISP than the 2024 Yankees—and that is by design.

The highlights:

- The Yankees hit 59 home runs in August. Only the 2019 Yankees ever hit more in the month. Thirty-two teams have hit 50 homers in August. The Yankees did it with the fewest hits (227).

- The Yankees have the biggest increase in fly ball rate (+3.9%) in MLB, the greatest average bat speed (73.1 MPH), the second biggest increase in launch angle (+2.7%, behind only the White Sox) and the highest fly ball rate other than the Dodgers.

- The four teams who hit the most fly balls (Dodgers: 31%; Yankees: 30.6%; Cubs: 29.8%; Tigers: 29.3%) are all in playoff position, led by the Dodgers, who lead MLB in fly ball rate for a fifth straight year:

- The team that is last in fly balls? That’s the team with the best record in baseball, the Milwaukee Brewers (22.8%). They zig while everyone else zags.

- The Yankees have increased their reliance on hitting the ball in the air, as an incredible 13-game stretch to close out last month showed; they hit 38 home runs compared to 30 ground ball hits and 118 fly balls compared to 117 ground balls over that span.

Why and how are the Yankees leaning into this style of hitting? Here are some of the underlying reasons.

1. The Yankees sacrifice contact for power.

It sounds heretical, but RISP and strikeouts are overrated in today’s hitting world. RISP often is misused. The industry has devalued batting average and yet it still gets used in RISP. Move a runner over from second base with no outs or get someone in from third base with less than two outs on a fly ball and neither helps RISP batting average.

When the Yankees led the world in home runs in August, they were 17th in RISP (.253), 20th in batting average (.221) and 26th in strikeouts (263). And they were 16–12.

New York is far worse this season than last at making contact and RISP, which sounds like a problem but it’s not. It’s a tradeoff they make willingly to hit that magic threshold of two home runs per game.

2. It’s all about the second home run.

Being a one-path-to-victory team is risky. If their opponent keeps them in the park, the Yankees are in trouble. This breakdown defines how important the home run is to New York.

3. The Yankees are swinging up on the ball much more than last year.

Yankees hitting coach James Rowson and assistants Casey Dykes and Pat Roessler are masters at teaching controlled aggressiveness: limit chase, but when you get a pitch in your zone don’t hesitate to put your “A” swing on it. And this year, that “A” swing includes a mechanical emphasis to bring the barrel to the baseball on an upward track.

Here is how much the Yankees’ offensive approach has changed:

4. Yankee player acquisition and development are influenced by fly ball hitting.

Three of the five players with the biggest increase in fly ball rate this year are Yankees, two of whom were acquired last year or this year.

That’s not all. Austin Wells (+5.7%), Paul Goldschmidt (+3.2), Jose Caballero (+2.5) and Cody Bellinger (+1.8%) all have boosted their fly ball rates this year. That gives the Yankees seven of the top 61 fly ball increases.

VERDUCCI: How Former Top Yankees Prospect Anthony Volpe Became Unplayable

Bellinger started hitting fly balls as soon as he joined the Yankees in spring training. He moved closer to the plate—back where he was in 2019—and emphasized getting the ball in the air to the pull side, a skill he had lost. Now he is hitting more fly balls than ever in his career (36.7%).

Aaron Judge made his swing change in 2022, the year he hit 62 home runs, to get the ball in the air more. He has been a model of consistency since then in terms of keeping the ball off the ground using a 15° attack angle, well above the average of 10°, which you can see every time he takes a practice swing.

Over the past three years, Judge has grounded out to the right side of the infield just four times (not including topped balls in front of the plate fielded by the pitcher or catcher). He has not grounded out to first base since Sept. 21, 2022.

5. Jazz Chisholm is a good example of how the Yankees tailor swings to get the ball airborne.

Before he was traded to the Yankees, Chisholm was a ground ball hitter. Now he is an extreme fly ball hitter who, like Bellinger, is hitting a career-high rate of fly balls (36.3%, well above MLB average of 24%).

How did the Yankees do this? They changed the path of his barrel to the ball.

We can measure that path change with Statcast. Chisholm has increased both his attack angle and attack direction.

Think of attack angle as a vertical gauge—how far the barrel works in an upward plane to meet the ball. You can see in the measurements below that Chisholm is swinging in a more upward path to the pitch—much steeper than the MLB average of 10°.

Think of attack direction as a horizontal gauge. Chisholm made a major adjustment with his attack direction. Last year he was at 2°, which is the MLB average. He was a neutral hitter in terms of where he hit the ball. But this year his bat is moving much more in a path toward the right side of the field—hitting the ball out front. It is the path of a pull hitter.

Chisholm has hit a career-high 26 home runs. Here is what the changes look like in terms of data:

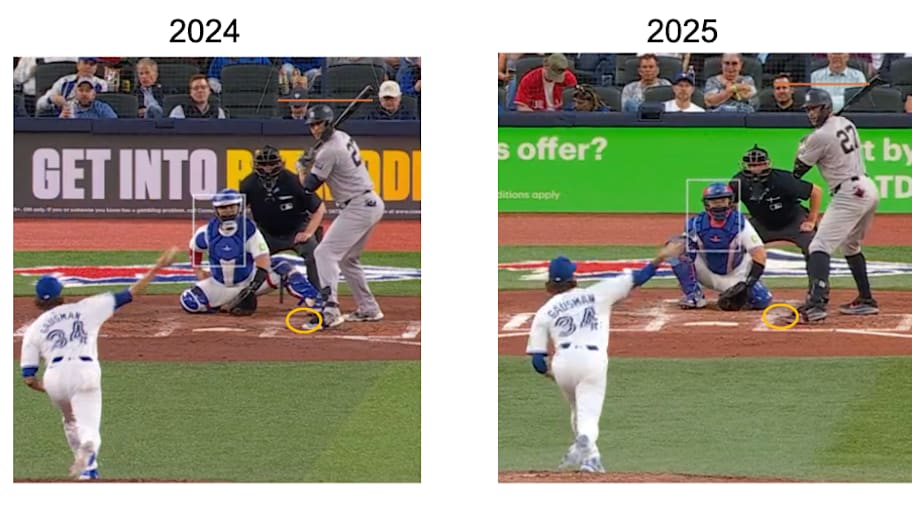

And here is what the changes visually look like. He is dropping the barrel lower as it enters the hitting zone so that he can swing up more on the ball. He is trying to catch the bottom third of the baseball and to hit it more out front of the plate, the better to generate pull-side balls in the air.

These are two nearly identical pitches: fastballs from a righthander down and middle. The one from last season is a ground ball single up the middle. The one from this season is a pull-side home run.

I highlighted the angle of his bat so you can see his descent angle is less steep this year, allowing him to work his barrel more underneath the baseball (greater attack angle).

The contact point pictures are somewhat similar, but the greater attack direction means he is catching the ball more in front and staying connected through contact, which you can see with how his hands and arms remain closer to his body.

6. Giancarlo Stanton jumped aboard the Airborne Baseball train.

Yes, even a 35-year-old, five-time All-Star with 446 career home runs has joined the fly ball party. Stanton always has hit the ball as hard as just about anybody in baseball. But he deployed such a flat swing he hit too many ground balls for a guy with so much power. Until last year, he hit balls on the ground at a rate greater than the major league average.

Those days are over. It’s only a 55-game sample, but Stanton is slugging at a rate (.624) topped only by his 2019 MVP season. He is hitting a career-low rate of ground balls (32.7%) and a career-high rate of fly balls (29.2%).

How is that possible at age 35? Like Chisholm, Stanton has learned to drop the barrel lower behind him and bring it to the hitting zone in a sharper upward angle. He is hitting the bottom third of the baseball more often—and when you do that with the highest average exit velocity in the sport, look out.

Those are the data. Now here is a visual to see how Stanton has changed his setup to get more underneath the baseball. Both pitches are splitters from Kevin Gausman. The one last year is a foul ball. The one this year is a home run.

Stanton has closed his stance farther. This year you can see the entire 7 of the 27 on his back. At foot strike/ball release, the stride foot is closer to the plate. And Stanton is in a more erect posture, which is more common among tall power hitters to create more leverage.

7. Trent Grisham and Ben Rice are having career years by … you guessed it, pulling the ball in the air.

Grisham hasn’t changed his swing. He hunts fastballs in the zone and is more apt to put a home run swing on it when he gets it. He has talked about how playing with Judge and Stanton has encouraged him to take more big swings, depending on count and situation. Grisham has reached career highs in pulling the ball and pulling the ball in the air while hitting a career-low rate of balls to the opposite field. And here is what every scouting report says about him: he devours fastballs.

Rice has almost the same profile: a pull-side, fly ball hitter who hunts fastballs:

Like or not, traditionalist or not, the Yankees do have a path to win the World Series by relying on getting the ball in the air and over the fence. What’s to stop them? An age-old antidote: a well-executed pitching plan.

Three of the five teams that have best limited the Yankees’ slugging this year are in playoff position and on their immediate schedule horizon: the Astros, Tigers and Red Sox. The Yankees begin a huge get-ready-for-October stretch Tuesday in Houston with the first of 12 straight games against the Astros, Blue Jays, Tigers and Red Sox.

The teams that have throttled the Yankees’ power have done so primarily by not feeding them four-seam fastballs and by boosting their off-speed use. The Yankees slug .497 against four-seamers, the best in the past two seasons except Arizona this year. The five teams who have pitched the Yankees the toughest all threw the Yankees fewer four-seamers than they usually see.

Meanwhile, except for Boston, they showed the Yankees more off-speed stuff than they normally see.

Yes, there is likely to be a game here or there where the Yankees don’t get a single with a man on second or strike out with a man on third and it costs them. It’s not to say the finer points of baseball are not important at all. Hey, all you need to do is go back to Game 5 of the World Series last year. The Yankees hit three home runs. They had been 16–2 in World Series games when they hit three homers, including 5–0 at home.

And they lost because they kicked the ball around on defense.

The Yankees bank on the finer points mattering less if they can hit the ball in the air and out of the park. The Brewers, who hit the ball on the ground, run and defend, have more ways to win. The Yankees choose the more narrow but easier path. To repeat the basic math: the Yankees take 69 swings per game. If two are home runs, they win 70% of the time. That’s why they swing up on the baseball.

The Yankees are the greatest show above earth. Can they be stopped? Of course. All you must do is keep them in the park.

More MLB on Sports Illustrated

This article was originally published on www.si.com as The Yankees Have Sold Out for Power, for Better or Worse.